Finding common ground by defining our differences: a useful map of public engagement discourses

Neil Stoker, Visiting Researcher at St. George’s University of London, found the landmark review of engagement studies by Jude Fransman in the latest issue of Research for All enlightening…

Neil Stoker, Visiting Researcher at St. George’s University of London, found the landmark review of engagement studies by Jude Fransman in the latest issue of Research for All enlightening…

Take any concept that you use freely (music, science, sport…?), try to define it precisely, and then ask someone else what it means to them. You might quickly find that you’re not quite as confident about its meaning as you’d thought, and that the other person sees it rather differently. So I shouldn’t be surprised to experience the same with ‘Public Engagement’.

Increasing awareness of Public Engagement

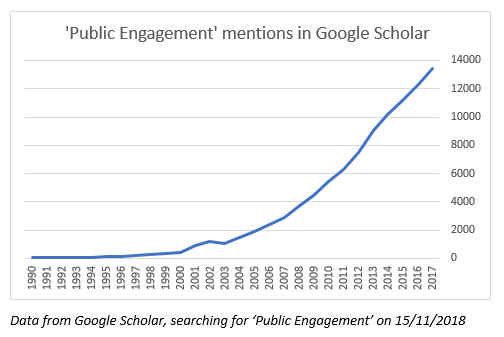

My own awareness of Public Engagement as an idea came from university biomedical science. I was told that researchers were working away, and generating knowledge that was changing society through new technologies. Other people – ‘the public’ – should be able to access this knowledge, both to empower themselves, and also to allow them to critique it. In my Science Communication MSc, I learned how the 2000 House of Lords Science and Technology report, concerned at a loss of trust in science following a series of environmental crises, called for scientists to engage with the public. The carrot and stick of conditional funding for universities followed, and Public Engagement became fashionable; see how annual mentions of Public Engagement in Google Scholar have risen from a handful to a barrow-load since then (Figure).

For me, Public Engagement has meant the need to open up the world of research and its findings, allowing people to explore the ideas in a variety of experiential ways, and encouraging conversations and dialogue. That included access to the literature and lay summaries, TV, festivals, museums, events, interacting with creative arts, and an openness on both sides about scientific process and interpretation; my ‘public’ was in a sense everyone.

Different definitions

However, I’ve become aware that that other people use the phrase ‘Public Engagement’ quite differently from me, to the extent that even having a conversation is difficult. For example, I talked to people using Patient and Public Involvement (PPI), and there was vanishingly little connection between us; so little indeed that it was hard to even identify any starting point for developing a relationship. I couldn’t connect with them, and they couldn’t connect with me. Others talked of Community Engagement as if it were similar, but in terms that made it seem very different.

I understood that there are different types of engagement, some more collaborative (as shown in the Wellcome Trust’s ‘Public Engagement onion’ diagram), but the disconnect seemed deeper than that. We talked across each other without meeting, and I didn’t understand why, or what to do about it. Furthermore, this seemed to have practical consequences, in that large amounts of time and money are involved, engagement is often a condition of funding, we are supposed to be working together towards strategic plans scattered with the term ‘engagement’, yet the confusion seemed to be growing rather than clearing.

Research engagement studies?

For me, that is where the excellent recent paper ‘Charting a course to an emerging field of ‘research engagement studies’: A conceptual meta-synthesis’ by Jude Fransman rode to my rescue. It’s a long paper with a long title, and the second half is beyond my expertise in that I scrabble to understand it, let alone have an opinion on it. But the first half was revelatory for me.

Essentially, Fransman maps the Public Engagement landscape in the UK, and – fully aware that any categorization is flawed – she divides it into what she calls five key domains. These are areas of significant activity, that seem to her to constitute coherent academic discourses; they are worlds that are grouped together as Public Engagement, but in fact each has its own history, culture, language, literature, understandings and aims, that may be very different from each other. Even when they use the same words, the meanings may differ.

Lonely Planet guide to Public Engagement

We relate to any map by first finding where we fit in, and I was struck by her Science & Technology domain, in that it described my own Public Engagement world quite precisely: the need for trust in science, the House of Lords report, terminology such as science communication and dialogue. Then I turned to her Public Policy Domain, and there was the PPI world that I was struggling to connect with, with almost no commonality in terms of terminology, discourses, formative literature, or framings.

This was a revelation because on that basis, I shouldn’t be surprised that I was finding it hard to connect these in my head, or in discussion. And it not only explained the disconnect, it also gave me a way in, because it also told me who they are, what language they speak, and how our cultures differ. It was my Lonely Planet guide.

As an experiment, I showed the paper to people working in Public Engagement whom I know to have very different backgrounds to me, and asked if they recognise themselves. And while there wasn’t a neat one-to-one agreement with the domains, they were able to place themselves, their backgrounds and current interests within that map. We could then have a conversation about those, and what they saw as currently important or difficult in their practices. There was also one domain – Higher Education – that is both a little different and also overarching. It describes the world from the perspective of university senior management, monitoring engagement through the REF, and providing evidence of impact. I thought it was useful to see this as its own domain, and perhaps useful for those managers to see the other domains through which these ends are achieved.

A tool for more effective communication

This paper was an intellectual tour de force, because to describe and map an academic landscape in this way is both a lot of work, but also requires breadth, flexibility and clarity of thought. After this mapping, the paper goes on to suggest theoretical aspects of engagement that might be relevant to all practices, so allowing more productive academic discourse about research engagement as a whole. I met and discussed the writing of the paper with Fransman, and she is the first to admit that her mapping might not be the ideal one, but for me this is a tool that I will return to, and it might just help those separate worlds not only to communicate more effectively, but also to learn from each other.

Reference: Fransman, J. (2018) Charting a course to an emerging field of 'research engagement studies': A conceptual meta-synthesis. Research For All 2, pp. 185-229. https://doi.org/10.18546/RFA.02.2.02

Contact

Neil Stoker is a Visiting Researcher at St George’s University of London, and Honorary Professor of Molecular Bacteriology at the Royal Veterinary College. The full transcript of the interview with Jude Fransman can be found here.